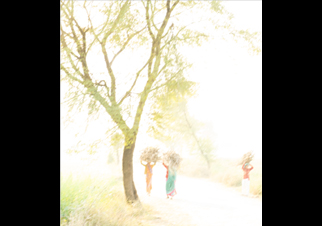

Harnessing technical expertise honed through his longstanding career as a photographer, Senthil constructs images of a different kind. Using the photographer’s slight of hand, he creates digital images that take on the appearance of watercolours with its painterly qualities of transparency and wash. The transfer of these reproductions onto handmade paper with deckled edges, further pushes this new body of work into the ambiguous territory between painting and photography.

This liminal state is further augmented by his return to a ‘truth to materials’ philosophy. None of the images in the show have undergone post-production processes such as the use of filters or effects in image manipulation software. In Senthil’s words: “Lighting in photography is like a paintbrush while painting.” Although driven by an essentialist use of the medium, Senthil destabilises fixed notions of medium specificity.

Historically, watercolour painting and photography have much in common. Before the invention of the camera, watercolours were used for reportage, ‘to render credible accounts of drawing what (reporters) saw and then adding colour.’ The use of photography in public and private life parallels the use of watercolour as a documentary tool and a recreational activity. Both watercolours and contemporary cameras are portable and offer easy accessibility, allowing these media to thrive in amateur and professionals circles. The modest scale of watercolours renders along with low lightfastness meant it was often hidden away in private folios. In this instance though, Senthil’s harnessing of light through photography creates unprecedented possibilities for public presentation in a multitude of scales.

Senthil was trained in the academic traditions of the Government College of Arts and Crafts, Chennai, India, which has historic roots in Company painting. The subject matter of this Indo-European hybrid style consisted of a repertoire of ‘exotic’ places, landscapes, festivals and people as a means to create visual records for commercial consumption. Senthil similarly presents picturesque themes such as village life, architectural monuments, cityscapes, portraits and still life, as a comment on the double bind integral in fine art and commercial practice. Challenging the cultural history of Company painting and its standard themes, parts of Senthil’s oeuvre portray carefully constructed images adopting new themes such as the body and queer identity, thereby undoing notions of ‘typical’ images.

At first glance, Senthil’s motivation to paint photography appears to stem from a place of nostalgia. It is however, driven by a desire for speed in a world constantly changing through innovation. Nudging viewers to confront our relationship to art in the wake of technology, Senthil’s work furthers critical dialogue around ideas of representational art and authenticity in global visual culture.