In the dark corners of nature, far from city lights and human eyes, organisms glow. Some flicker like fading embers; others pulse like neon signs underwater. This phenomenon, known as bioluminescence, is one of nature’s most hauntingly beautiful tricks. To witness it is one thing. To photograph it, especially up close, at extreme magnifications like 2:1, is another. Welcome to one of the most elusive and visually captivating niches of macro photography: the glowing world of bioluminescent life.

What Is Bioluminescence?

Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by a living organism. It occurs when certain enzymes (usually luciferase) react with molecules like luciferin, producing light in the process. Unlike fluorescence or phosphorescence, which require external light sources to charge and emit, bioluminescence is entirely self-powered. It’s a survival mechanism used for hunting, mating, camouflage, or communication.

The phenomenon is more common than most people think. It appears in deep-sea creatures, fireflies, certain fungi, bacteria, and even some land snails and millipedes. Yet, very few photographers have successfully captured this rare light at extreme close-up levels – especially at a magnification of 2:1 or higher, where even a few millimetres fill the frame.

The Challenge of 2:1 Macro

In macro photography, magnification refers to the ratio of subject size on the camera sensor versus its real-world size. A 1:1 ratio means your subject is life-size on the sensor. At 2:1, it is twice as large. This kind of magnification reveals details invisible to the naked eye, tiny ridges on insect wings, the fine fuzz on moss, the glistening spore structures of fungi.

Now combine that scale with a bioluminescent subject, likely active only at night, incredibly small, and dim by photographic standards, and you begin to see the scope of the challenge. You’re not just capturing a small glowing organism; you’re capturing it at high magnification, in darkness, without external light.

A Rare Cast of Characters: Bioluminescent Macro Subjects

Let’s look at some of the subjects that might grace the frame of a patient (and lucky) macro photographer working in this niche:

1. Fireflies (Lampyridae)

The most familiar glowing insects, and perhaps the “easiest” bioluminescent organism to photograph. While their bodies are larger than most macro subjects, photographing the actual light-emitting organ at 2:1 allows for abstract compositions of glowing tissue, textures, and colour gradients.

2. Railroad Worms (Phengodidae)

These beetles possess multiple glowing spots across their bodies—some red, some green. At 2:1, each glowing node becomes a separate frame-worthy subject.

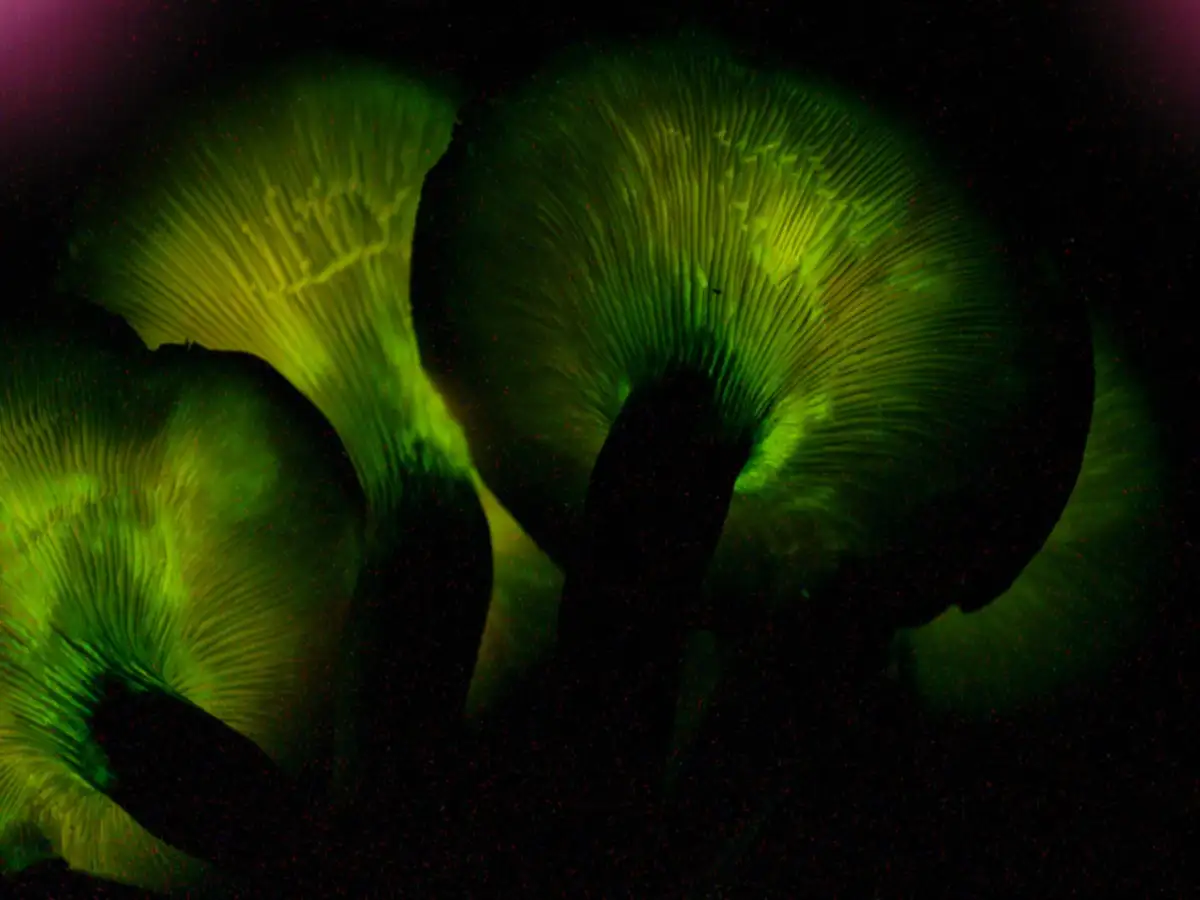

3. Bioluminescent Fungi (e.g., Mycena chlorophos, Panellus stipticus)

These glowing mushrooms emit a faint green light. Found in humid, decaying forests, their glow is often too dim for the human eye, but macro lenses and long exposures reveal stunning radial gill patterns and spore surfaces.

4. Marine Plankton and Dinoflagellates

Usually photographed in large-scale beach scenes, these single-celled organisms emit brilliant blue light when agitated. But under controlled lab conditions (and with serious patience), their bioluminescence can be observed and captured in isolation at high magnifications.

5. Bacterial Colonies (e.g., Vibrio fischeri)

These microbes glow as part of a symbiotic relationship with marine life like squid. Cultured under lab conditions on petri dishes, their colonies can be viewed at high macro magnification—revealing granular structure and shimmering wave-like patterns.

The Technical Hurdles

Capturing bioluminescence at 2:1 magnification is an extreme technical challenge. Here’s why and how a determined photographer might overcome the odds:

1. No External Light Allowed

By definition, bioluminescence must be shot in the dark. Unlike traditional macro subjects, you can’t use a flash, LED, or even a dim modeling light without washing out the glow. You’re forced to rely entirely on the emitted light.

Solution: Use long exposures—often 30 seconds or more—with high ISO settings. Multiple exposures may be required and stacked to reduce noise.

2. Minuscule Light Source

Most bioluminescent organisms emit extremely faint light. What looks magical to the eye is often too dim for a sensor.

Solution: Shoot with the fastest possible lens (f/2.8 or wider), and consider using image intensifiers or highly sensitive astro-modified cameras. Some researchers use cooled sensors for scientific imaging.

3. Shallow Depth of Field

At 2:1, even at f/8, your depth of field is razor-thin. But stopping down means losing light—already in short supply.

Solution: Focus stacking is one way around this, but it’s difficult with live subjects. Alternatively, you can embrace the shallow DOF and shoot creatively, emphasising a single glowing plane of focus.

4. Subject Motion

Many bioluminescent subjects are alive and moving – fireflies twitch, fungi sway in the breeze, bacteria multiply.

Solution: Stability is a key. Photograph in windless environments (ideally indoors), use remote triggers, and isolate your subject physically. With fungi and bacteria, create a dark lab-like environment to minimise disturbance.

Why It’s Worth the Effort

When it works, it’s spellbinding! Imagine seeing the tiny gill ridges of a glowing mushroom, radiating green like stained glass. Or the bioluminescent organ of a firefly, not just as a dot of light in the night sky—but as a textured, pulsating structure that looks like an alien gem. These images are not just rare—they’re revelatory. They expand our understanding of life and energy and demonstrate that beauty often hides at the intersection of science and patience.

Moreover, these photographs are powerful visual tools. They connect audiences with the wonder of the natural world. In conservation, bioluminescent fungi and insects are often used as flagship species to raise awareness about deforestation, soil health, and biodiversity. Macro bioluminescence photography can play a role in that education—bridging the gap between wonder and responsibility.

Final Thoughts

“Bioluminescence at 2:1” is more than just a technical challenge. It’s a frontier. It represents one of the most poetic and elusive forms of visual storytelling available to photographers. To pursue it is to slow down, experiment, and often fail. But the reward is a window into life’s quietest glow—a glimpse into the deep biological mysteries that surround us, mostly unseen.

As camera technology evolves and image sensors become more sensitive, this rare niche may become more accessible. But for now, it remains one of the most difficult and magical pursuits in all of macro photography.

In a world increasingly flooded with artificial light, perhaps the most valuable images are the ones that show us the natural light still flickering in the dark.