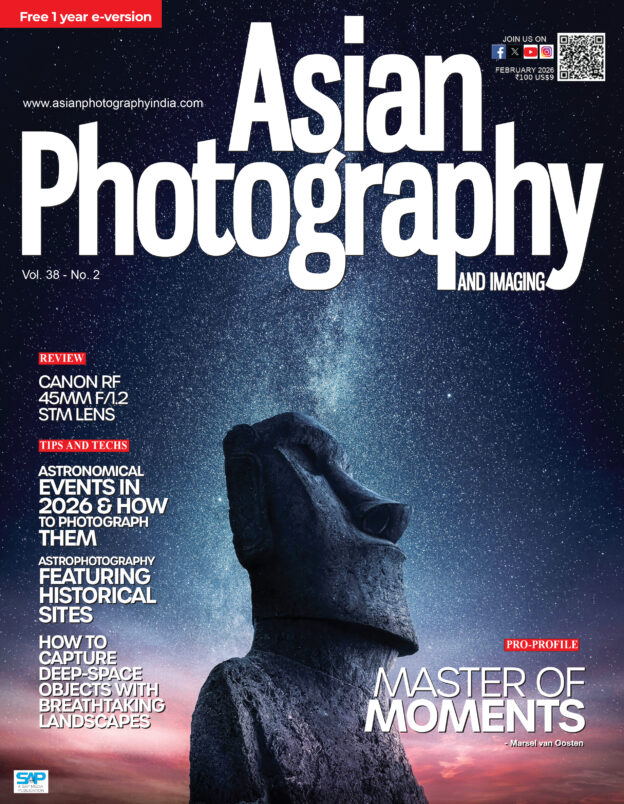

Marsel van Oosten is an award-winning photographer known for his profound artistry, especially his striking wildlife portraits. His work often blends the grandeur of landscapes with the intimate presence of wildlife, revealing the delicate balance of nature. His photographic style and thought-process has earned him critical acclaim, as well as the Wildlife Photography of the Year award. Asian Photography spoke to him about conservation, AI vs authenticity, lessons from the field and more.

For Marsel van Oosten, the path to becoming one of the world’s most recognised wildlife photographers was not paved with an early obsession for the camera. In fact, while studying art direction and graphic design at art school, photography was a medium he openly disliked. It was only after entering the professional world as an art director at an international advertising agency that he began to appreciate the profound power of still images. Tasked with selecting photographers for global ad campaigns, he was forced to dissect various styles and visual languages. Over 15 years, he collaborated with hundreds of top-tier photographers, treating every interaction as a masterclass. Eventually, this professional observation turned into a personal pursuit, though his first attempts during holidays were met with frustration. With a designer’s eye, he knew exactly what a “good” photograph should look like, but he lacked the technical vocabulary to execute it. This led to a period of intense self-education through amateur photography magazines, where he mastered the fundamentals before a honeymoon to Tanzania—his first safari—permanently shifted his focus toward the wilderness.

“The biggest threat to our planet is the idea that someone else will save it”

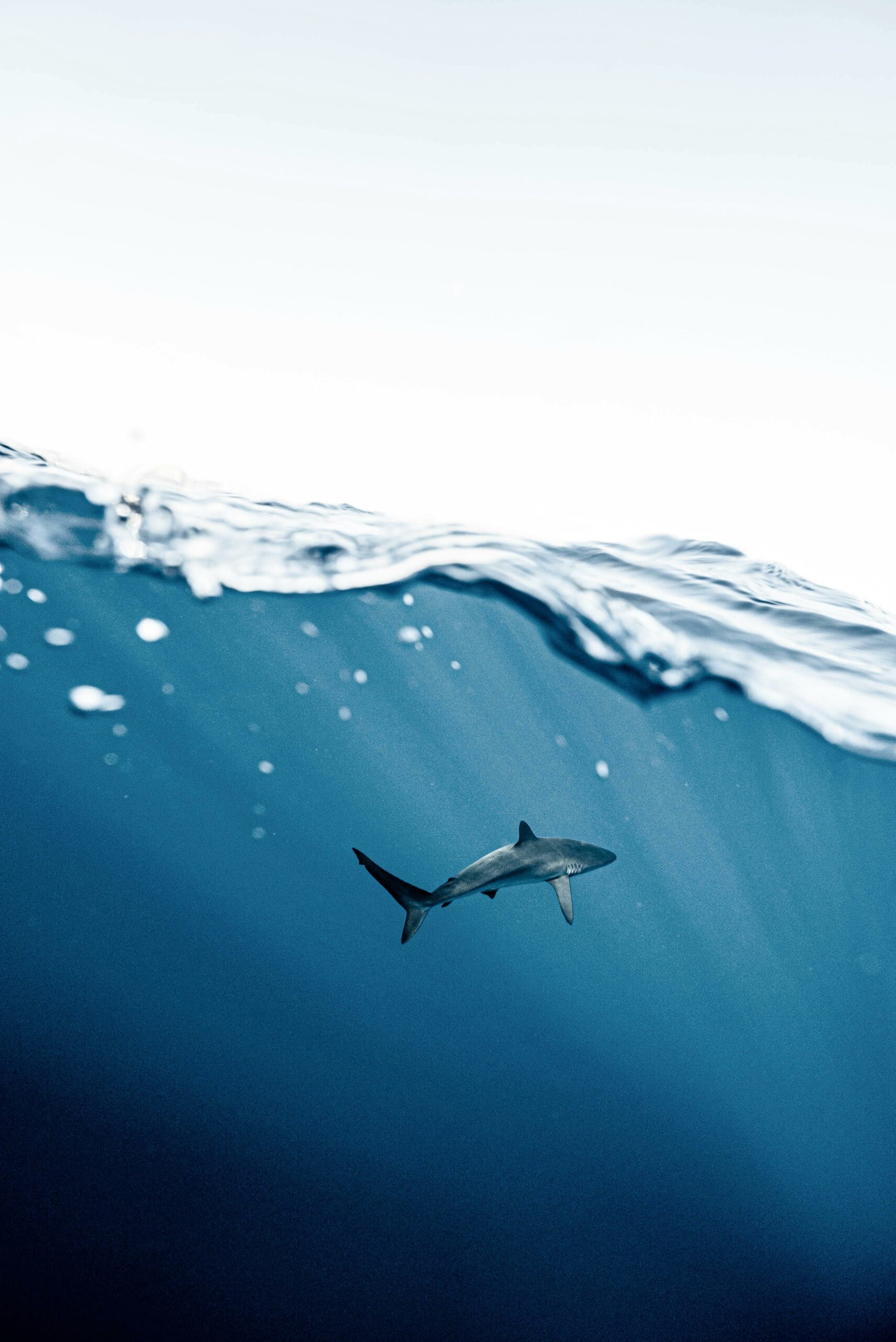

When reflecting on the motivations behind his transition into wildlife and conservation, Van Oosten explains that his travels have allowed him to witness a world in a state of rapid decline. He notes that with each passing year, more species are pushed toward the brink of extinction while ecosystems are systematically destroyed or polluted. His work is fuelled by a desire to inspire a sense of urgency in the viewer, grounded in the belief that “the biggest threat to our planet is the idea that someone else will save it.” He describes a “global narcissism pandemic” fuelled by social media, where the hunt for “likes” has turned into a destructive force. He points to the Masai Mara as a tragic example of how greed, corruption, and unsustainable “selfie tourism” can lead to conservation disasters. While he acknowledges that social media has occasionally amplified conservation efforts, he remains wary of how the unhinged pursuit of a “cool shot” often overlooks the welfare of the animals and the integrity of the environment.

When asked how he would define his specific photographic signature, Van Oosten emphasises a rejection of current trends in favour of an internal creative compass. In a field as saturated as wildlife photography, he finds that staying true to reality while avoiding excessive processing is the ultimate challenge. His style is an extension of his character: a relentless pursuit of order within chaos and a deep-seated aversion to visual clutter. Drawing heavily from his graphic design background, he prioritises graphic shapes, balanced lines, and clean compositions. He avoids what is popular, choosing instead to document subjects that inspire him personally, which he believes is why his work often feels fresh to the public. Central to his signature is the “idea” behind the frame. Because photographers have little control over wild subjects, he invests heavily in research and pre-visualisation. Before a shoot, he studies existing imagery of a subject specifically to ensure he does not replicate it, planning his trips with clinical precision to capture the specific image already living in his mind.

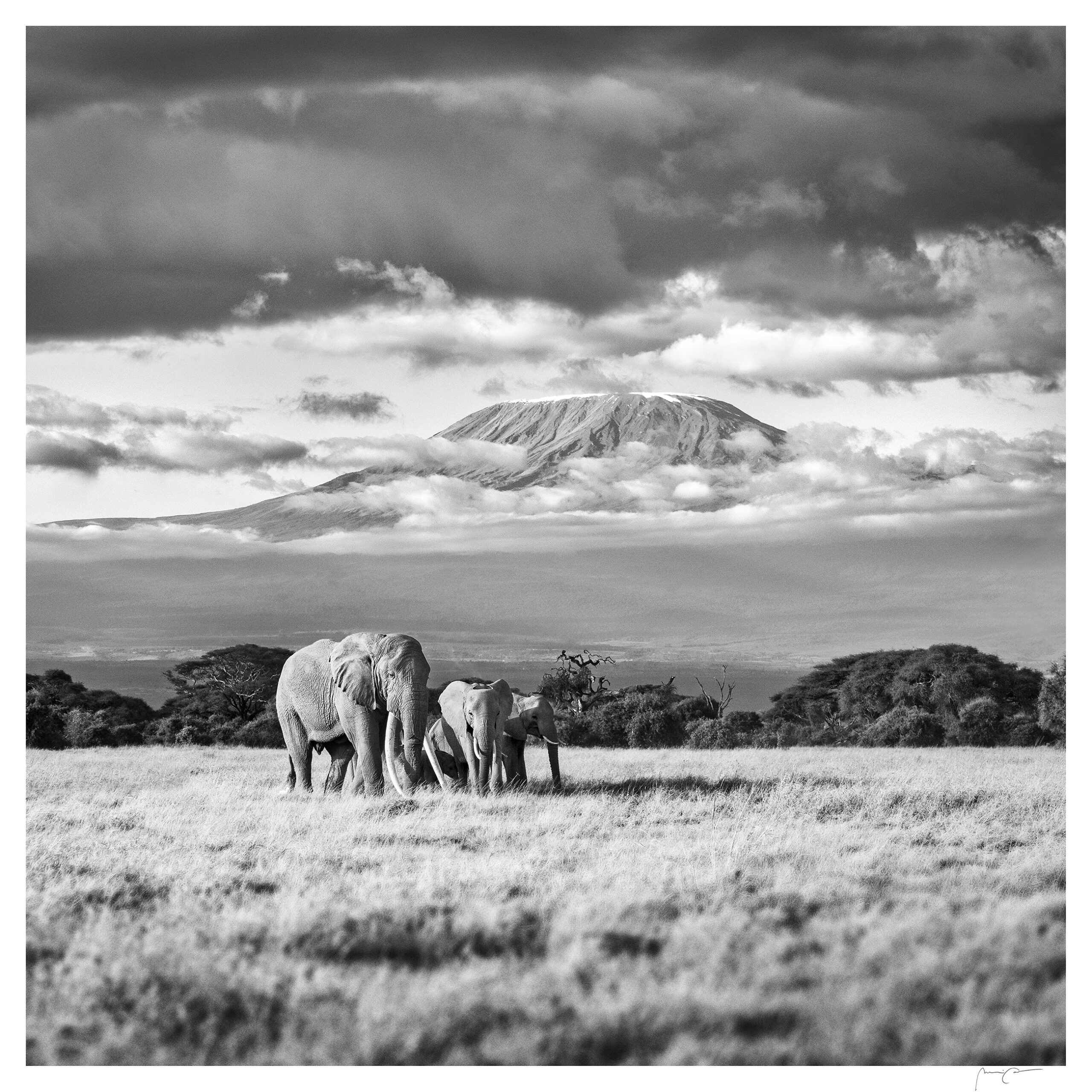

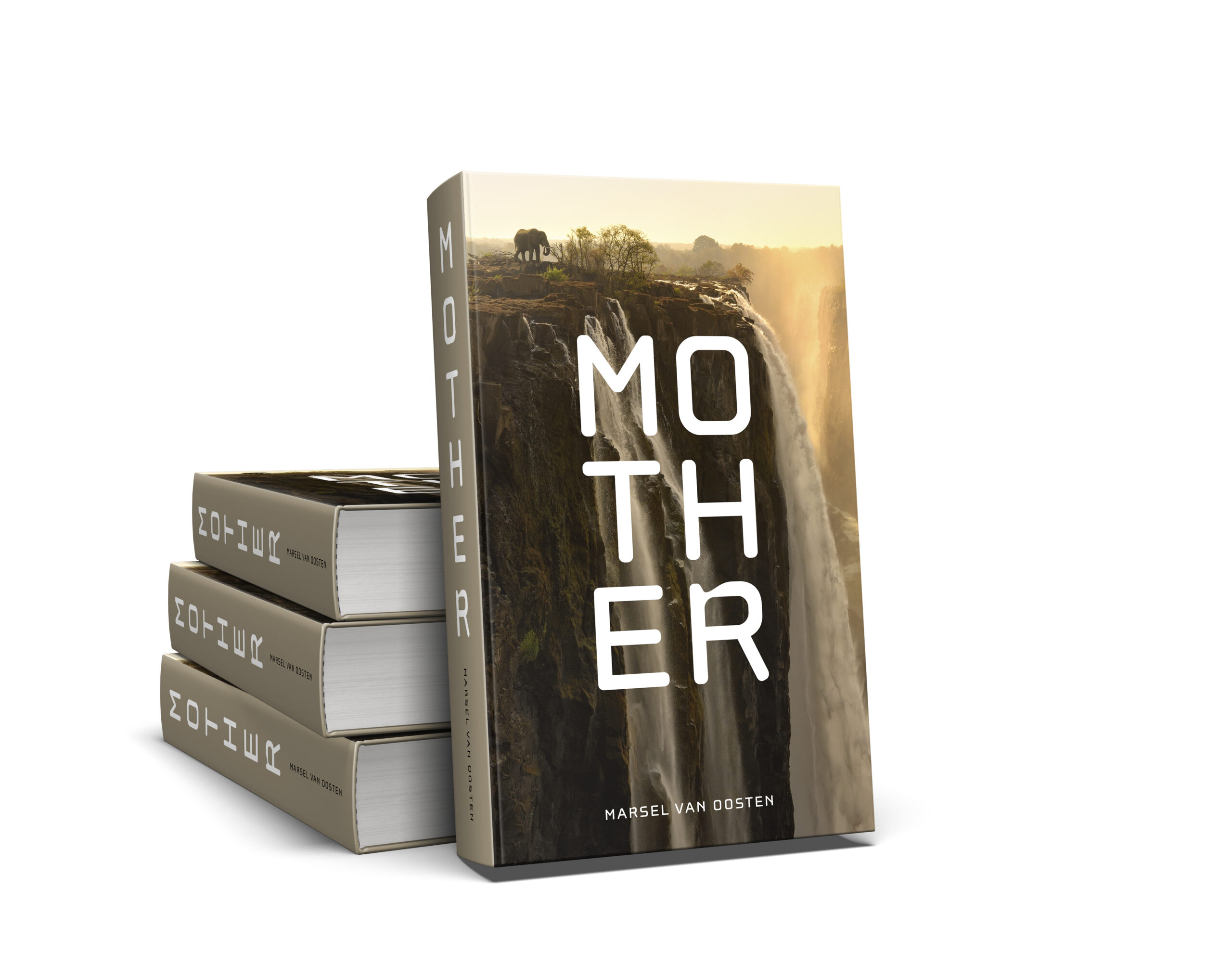

Regarding the specific image that might define him as a photographer, Van Oosten points to the cover of his book, MOTHER, which features an elephant standing at the very edge of Victoria Falls. This particular shot, which was one of his first publications in National Geographic, serves as a bridge between his two primary passions: wildlife and landscape. He notes that while both genres require vastly different skill sets, his favorite work often exists at their intersection—a landscape image with a strong wildlife element. For him, the Victoria Falls elephant represents “perfection” and acts as a visual manifesto for his entire career.

The conversation naturally shifts to the technicalities of the digital darkroom. When asked about the extent of his post-processing, Van Oosten compares the role of a photographer to that of a Michelin-starred chef. A great chef uses the best ingredients, but the mastery lies in creating a dish that is more than the sum of its parts—achieved through a “creative sauce” of herbs and spices. In his world, post-processing is that sauce. However, he strives for a result that looks entirely unprocessed and natural, a feat he describes as being much harder to achieve than applying a standard filter or preset. He is obsessed with subtle details that most viewers may never consciously notice. His process is one of patience; he refuses to publish an image immediately after a first session, knowing that a fresh perspective the following day will inevitably reveal necessary refinements. He critiques photographers whose styles are built entirely on heavy colour treatments, arguing that if one removes those filters, the underlying images are often mediocre. For Van Oosten, a truly memorable image must stand on its own without the crutch of digital manipulation.

The rewards of such a high-stakes career are often tempered by unforeseen consequences. When discussing his most rewarding moment in conservation, he recalls winning the overall title of “Wildlife Photographer of the Year” for his image of golden snub-nosed monkeys. At the time, the species was largely unknown to the general public. The image went viral, appearing in newspapers and exhibitions across the globe, successfully generating the awareness needed to secure funding for their protection. Yet, he speaks candidly about the “double-edged sword” of such fame. The surge in awareness created a massive demand for tourism in a fragile Chinese ecosystem that could not sustain the influx, ultimately forcing the area to close. This realization has changed his approach, making him far more secretive about the locations of fragile ecosystems to prevent his own work from inadvertently causing their downfall.

In the modern era, the conversation inevitably turns to technology. When asked how he promotes authenticity in the age of Artificial Intelligence, Van Oosten offers a perspective that often sparks heated debate. He leans on his art school education, asserting that in art, there are no rules. He distinguishes between “functional” photography—such as forensic, scientific, or news photography—which must adhere to strict reality, and photography as an art form, which includes nature. While he personally prefers to stay close to the scene as he witnessed it, he holds no grudge against those who use AI or heavy manipulation to realise a creative vision. He predicts that many genres will lose the “battle” against AI because it allows creators to achieve what wildlife photographers never could: total control over the subject. While many argue that AI-generated images lack soul or connection, Van Oosten is more pragmatic, stating that for him, it is always about the end result. He views the “trust” people place in cameras as a historical accident, noting that we don’t question the integrity of a Rembrandt painting just because it isn’t a literal photocopy of a scene.

“Authenticity is not relevant in art, and I don’t think a photographer has a responsibility to disclose how the work was made”

Finally, when asked about the most important lesson he has learned while shooting in some of the harshest conditions on Earth, his answer is surprisingly simple. Beyond the technical mastery, the gear, and the conservation goals, he has learned to enjoy every single moment spent in the wilderness. He acknowledges the privilege of existing in a world of such spectacular biodiversity. Even on the days when the light is poor, the animals are elusive, and he doesn’t capture a single frame, he remains deeply grateful. For Van Oosten, the primary goal is never to take those moments for granted, recognising that being a witness to nature is a reward in itself.