The world of landscape photography is currently at a crossroads. For decades, the recipe for a “great” photo has been fairly rigid: find a famous mountain, arrive at sunrise, set your tripod to a specific height, use a wide-angle lens, and wait for the “hero light”. But in 2026, we are witnessing a quiet revolution. As artificial intelligence becomes capable of generating “perfect” sunsets with a single tap, the value of that technical perfection is plummeting.

If a machine can create a flawless vista of the Himalayas, why do we still trek for days to see them? The answer doesn’t lie in the pixels; it lies in the presence.

The “Sentient Landscape” is a philosophy that moves away from the hunt for the perfect shot and toward a deeper, more visceral relationship with the world around us. It’s about slowing down, embracing the “messy” reality of nature, and using your camera not just as a recording device, but as a sensory bridge. Here is how we redefine the craft for an era that values soul over sharpness.

Finding Poetry in the Small Stuff: The Intimate Landscape

We have been conditioned to think that “landscape” means “everything”. We reach for our widest lenses to cram as much of the horizon into the frame as possible. But there is a profound, quiet power in doing the exact opposite.

The Intimate Landscape is the art of extraction. It’s about using a telephoto lens—the kind you’d usually use for birds or sports—to zoom into the patterns of the earth. When you remove the sky and the horizon, you remove the context of scale. A ripple in a sand dune can look like a vast desert; the bark of an ancient tree can look like a topographical map of a canyon.

By looking for the “landscape within the landscape”, you stop being a tourist and start being an observer. You begin to see rhythms, textures, and shadows that the “hero shot” hunter misses. It’s the difference between hearing a symphony and listening to the vibrato of a single violin string.

Painting with the Cosmos: Astro-Landscape Impressionism

Astrophotography is often the most technical, rigid genre of them all. It’s usually about noise reduction, star tracking, and pinpoint sharpness. But the stars aren’t just cold dots of light; they are ancient, pulsing energy.

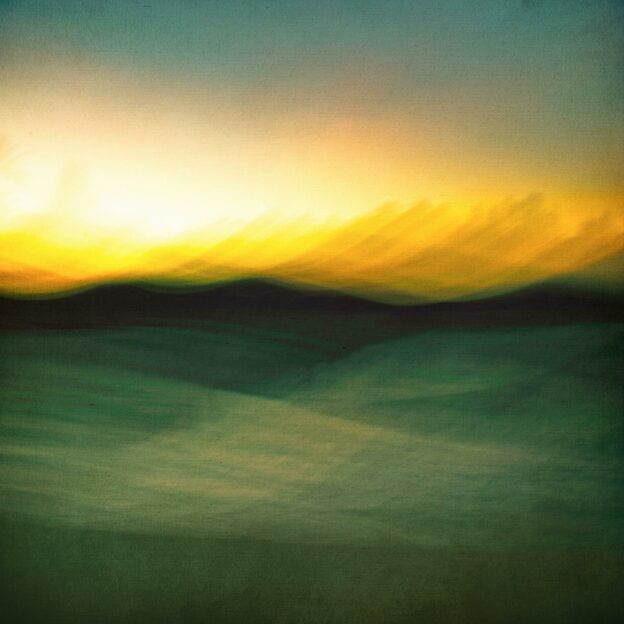

Astro-Landscape Impressionism – specifically through a technique called Intentional Camera Movement (ICM) challenges the “sharpness” rule. Imagine standing under a brilliant night sky, perhaps with Jupiter or the Milky Way burning bright above you. Instead of locking your camera down on a heavy tripod, you hold it. As the shutter stays open for a few seconds, you move the camera with a slow, deliberate rhythm.

The result is a dreamscape. The stars turn into streaks of light, blending with the silhouettes of trees or mountains. It looks less like a photograph and more like a painting by Van Gogh or Monet. You aren’t capturing the geometry of the night; you are capturing the feeling of standing under the infinite. It’s a way of saying, “This is how the night felt to me,” rather than “This is what the night looked like.”

The Atmospheric Protagonist: When Weather Becomes the Hero

How many times have we checked the weather forecast, seen “cloudy and rainy”, and decided to stay home? In the conventional world, rain is a nuisance. In the Sentient world, the storm is the story.

When we wait for the “perfect” light, we are essentially asking nature to perform for us. But the most honest moments in nature are often the most difficult. A mountain peak that is half-hidden by a heavy monsoon mist is infinitely more mysterious than one under a clear blue sky. A forest floor during a grey, drizzly afternoon has a depth of colour—a “neon” green to the moss and a deep obsidian to the wet rocks—that a bright sun would simply wash out.

“Weather as the Hero” means leaning into the low contrast. It’s about realising that fog isn’t hiding the landscape; it is the landscape. It adds a sense of “Soft Fascination”, a psychological state where our brains can rest and recover by looking at the gentle, repeating patterns of nature without the harsh glare of a “hero” sun.

With all that being said, we’d advise not going out in bad weather, such that it can cause damage to your equipment or harm to you, just to try and get a “good” shot.

The Intentional Pause: The Psychology of Not Releasing the Shutter

The biggest barrier to great photography in 2026 isn’t bad gear; it’s the digital trigger-finger. We take thousands of photos, hoping that one of them will be “the one”. This “spray and pray” method actually disconnects us from the very place we are trying to capture.

The most avant-garde advice for a modern photographer is simple: Stop shooting, or to be more precise, stop shooting as much.

Practice the “Five-Frame Limit“. Go to a beautiful location and spend three hours there, but allow yourself only five clicks of the shutter. What happens to your brain when you do this is fascinating. You stop looking at your screen and start looking at the land. You notice the way the wind moves through the grass. You feel the change in temperature as a cloud passes. You hear the distant call of a bird.

When you finally decide to press the button, that frame carries the weight of those three hours. It isn’t just a picture; it’s a memory that has been carefully selected and refined by your own presence. This is what it means to “shoot with intent”.

PS: Film photography is totally not dead, try taking it up if you’re struggling with the issue of the digital trigger-finger, and have got some coin to spare.

Vying For An Authentic Future

As we move further into a world of digital perfection, Sentient Landscapes offer a path back to what makes us human. It reminds us that photography isn’t about the gear we use, it always has been about the way we choose to see.

By embracing the intimate, the impressionistic, and the atmospheric, and by slowing our pace to match the rhythm of the earth, we create images that are uniquely ours. They might not be the “cleanest” or the “sharpest” shots on social media, but they will be the most honest.

In 2026, the most radical thing you can do as a photographer is to stop trying to be a machine and start trying to be a soul in the wilderness.